The following is a true story. Only the country’s name has been changed to protect the stupid. There is, however, one tiny little falsehood. See if you can find it.

Like I said, this is a true story. Except for the one little fib mentioned above (can you find it?), the only thing changed is the name of the country, which I am calling Stupidistan. I could have made it Don’t-have-a-clue-istan or Don’t-give-a-darn-istan or Oblivioustan or something similar, but Stupidistan will do.

Now, here is the story:

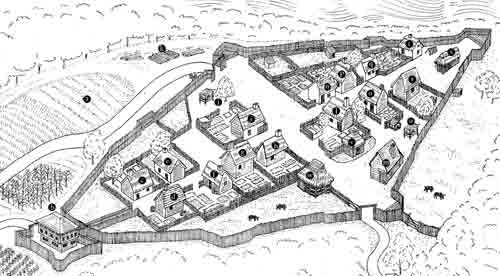

Once upon a time there was a new country. It was a largely agrarian country in which the people made a living by farming supplemented by hunting and fishing in the off-season. Early in its founding, the rulers of the country tried dividing everything produced equally among the people with no regard to who produced what, nor how much. The result was that the new country almost died aborning. Why? Because, quite simply, of human nature. People noticed that those who did little, or no, work, received the same amount as those who worked. Moreover, those who were inefficient producers received the same as those who were the most efficient producers. So the hardest workers and most efficient producers began to wonder why they should continue to work so hard to produce extra, when that extra was just going to be confiscated and given to someone who didn’t work as hard, or worse, didn’t work at all. Completely natural and understandable behavior.

The result was that production languished to the point where the people of the little country almost starved to death. Concerned for the continued viability of their country, the elders met in an assembly in order to determine what course of action to take. Among the assemblymen might have been a very wise man who recognized that the “share and share alike” plan was the problem since not only was it contrary to human nature, but it also violated one of the “natural laws” — that each man was entitled to the fruits of his own labor, ingenuity, and industry.

The man shared his belief with the others, and a spirited debate ensued. Questions were raised like “What about the sick and infirm who cannot work?” and “What about those who are not as efficient as others?” and “What about widows and orphans?” Naturally, these were all good questions, which I suppose that the man might have addressed in the following manner:

“My fellow assemblymen and settlers, we all know that there are those who, due to their gifts of good health, strength, and wisdom, are better producers than others. That was true in that land from which we all came, and it remains true here. Some people are just not as good at raising crops and at hunting as others. Then, as some of you have rightly mentioned, there are widows, orphans, and the sick who cannot produce at all. Do we allow them to starve just because fate may not have smiled upon them as she has upon others? Of course we do not, but allow me, if you will, to return to that in a bit.

“We came to this new land for a number of reasons. In the land where most of us originated, we could not own property. Here, we can. There, much of what we produced was taken from us as tribute to the nobility of the land. Here, we have the opportunity to create a country in which no man can lord it over another and in which every man has the right to to keep that which he produces, so we must now ask ourselves if that would be a good thing?

“The answer to that question will be found, I believe, in two parts. First, let us all hearken back to those conversations that took place when we first considered coming to this new land and to endure its hardships in order to create our new country. You will recall that there was much talk about “natural rights” — those rights that come to us from our Creator and can neither by man be granted nor by him taken. You will recall, also, that one of the rights so recognized was that of every man to the fruits of his own industry.

“If that is, in fact, a natural right, then I would suggest that we have surely violated it by taking from those who produced more and giving to those who produced less. How can we expect success, if we start out by violating that which we all agreed should be upheld at all cost? If natural rights truly come from God, then should we expect Him to look kindly upon those who take His gifts so lightly? And why, I would ask, would we want to allow the oppressions of that other land, from which we have only recently extricated ourselves, to follow us here?

“Secondly, we have only to look to history to see example after example where true prosperity for all was achieved only after society made laws respecting both human nature and natural rights by allowing individuals to prosper, or not to prosper, based upon their own gifts, abilities, and choice. It is so absolutely clear that it is the best way to ensure maximum production from available resources and, therefore, maximum prosperity for all, that one must wonder why societies continue to try otherwise? Yet they do. We have seen it yet again, my friends, right here, and we have also seen the result. Old notions, no matter how often proved wrong, do, indeed, die hard.

“It seems to me that, if we wish to ensure the survival and prosperity of this new country — both of which are today in dire jeopardy — then we must humbly and contritely return to those principles that we valued early on but from which we have recently strayed. Would it be a good thing to make this a country wherein each man is entitled to his own production? We know that it would.

“Now, please allow me to return to the question of providing for those who cannot provide for themselves. What we are talking about is the possible transfer of a part of the production of those who can, and do, work and produce to those who, for whatever reason, cannot. To put it another way, it would be a transfer of goods from those who have a natural right to the goods to those who have no such right. My friends, there is a word for such transfers, and that word is charity. All in this new land are Christians, and we have been taught, and continue to teach our children, that charity is a basic duty of us all. Let us not shy, therefore, from calling charity what it is, as charity is as necessary for those who have a duty to give it as it is for those who have a need to receive it. Just as receiving cannot happen without giving, neither can giving happen in the absence of those with a need to receive. Our question now becomes, not whether to provide, as we most certainly should, but how it should be accomplished?

“One way to accomplish the objective of providing for the less fortunate would be to enact a law to require that every man give a part of his production to the government which would then distribute it to those in need, but, how, I would ask, could such a law be just if it would serve to negate that gift from God which I have mentioned several times already — the right of every man to the fruits of his own labor and by extension thereof, the right to decide upon its disposition? I would suggest that, had we the desire to be subject to unjust laws, then we did not have to come here at great expense and hardship in order to be so. Also, since such transfers would not be voluntary, they could not be considered charity and could not, therefore, satisfy our charitable duty but would, instead, only add to it.

“Furthermore, such coerced transfers are necessarily doomed to failure for other reasons, such as:

1. A not inconsiderable portion of all that is transferred to the government would disappear to graft, corruption, and waste.

2. The end would become perverted from the need to provide for the unfortunate to the need of government to increase its own power, and grants would be made based not upon what is best for the people, but upon what is best for the government.

“Once again, we have only to consult our faithful and persistent, but oft neglected, teacher, history, to know that these predictions, unfortunately, always come true.

“There is, however, another way to effect the providing for those who cannot provide for themselves, and that is to allow every man to choose, according to his own perception and understanding of his charitable duty, what and how much to give and, indeed, even whether to give. Not only is this the only way to accomplish the provision for others without violating the giver’s natural rights, but history has shown us time and again that a good people, when allowed complete discretion over their own resources, will always share with others less fortunate than they to the extent that it would be rare for anyone to be found wanting the basic necessities for life.

“But charitable duty, we must never forget, requires only that we assist those who cannot provide for themselves, not those who can but choose not to. The fates of the last we should leave to themselves, to nature, and to God.”

Fortunately, the man was passionate, scholarly, and well spoken, and he was able to move his fellow assemblymen to the point where they could see the logic and truth in what he said. As a result, the people went on to create a contract that recognized human nature and respected natural rights, and this contract was later adopted as the charter for the young country. Due to the great amount of individual freedom that the contract provided, the ensuing years brought quick and steady progress so that the little country grew and eventually became one of the wealthiest nations, for its size, in the world, surpassing even countries much much older than itself. It became so that even its poorest people were better off than many who were considered to be “middle class” in other countries.

As it so often happens, though, this prosperity did not come without cost. The people became, over time, complacent in their plenty and neglected to give their freedom the constant care and nurturing that it required lest it become sickly and perish. Most forgot the lessons of history. Those who did not forget regarded them as outdated and old fashioned and ignored them. Politicians discovered that they could gain votes by promising certain groups benefits from the public treasury. That this violated the natural rights of others was either not recognized or not cared about. As a result, the numbers of the recipients of government’s largess grew over the years to the point where the people living off the government came to outnumber those who were contributing sizable portions of their production in taxes.

Well, you can imagine how this story ends. Once the numbers of those paying no taxes, and therefore having no stake in (and no reason to oppose) tax increases, became greater than the numbers of those actually paying taxes, the days of the country became numbered, and it was only a matter of time before it completely self-destructed. The non-taxpayers continued to vote larger and larger tax burdens upon the taxpayers until they either left the country, found ways to hide their income, perhaps by taking their businesses underground, or just quit producing so much. All respect for the law was lost. The leaches saw their livelihoods shrink and then disappear, and they were not happy. The country spiraled into revolution and anarchy. The end was not pretty, but, then, it never is. The irony of the whole matter is that the course was entirely predictable and, therefore, preventable.

You’re probably thinking that Stupidistan is an entirely appropriate name. What dummies! They were delivered out of socialism and went on to become a great nation. Why would they fall back into it?

Why, indeed?

Surely, the story bears a few stretch marks, but it is, as I said, (mostly) true except for the one exception. So, do you think that you have spotted the single little fib in this story? If so, then please share it by commenting upon the article. All will be revealed in Part 2 in a few days.

Jere Moore has been blogging about political matters since 2008. His posts include commentary about current news items, conservative opinion pieces, satirical articles, stories that illustrate conservative principles, and posts about history, rights, and economics.