In order to understand inflation, we must first understand money. Trouble is, we don’t, so, time after time, we fall for the same old Keynesian schemes. As a result, we become poorer year after year, while people we don’t even know steal, via inflation, our asset values from us and effectively loot our retirement accounts.

The following explanation of the evolution of money is pretty simplistic and given from memory of things that I read in the past, so don’t hold me to the details. I didn’t, after all, actually witness these things. Even so, it is, I believe, an accurate account of …

The Evolution of Money, both Real and Funny

Here we go …

What is money?

I’ll bet you two things:

1. You think you know, and

2. You don’t.

We shouldn’t feel too bad, though, because it’s difficult to learn that which we aren’t taught, or even had actively hidden from us, and this kind of thing is not taught in any public high schools in America.

In the beginning

In the beginning, God created … no, that’s another story. For this one, in the beginning, there was barter. We took that which we had an abundance of and attempted to trade it for that which we didn’t have an abundance of and needed. By and by, to facilitate such exchanges, regional markets would develop where everyone could take their stuff to trade for other stuff.

This would allow for specialization – rather than grow or produce many different crops or products, everyone could grow or produce just that which they were the best at, and then, in the market, they could trade for all kinds of other stuff, so specialization, along with easy trade in free markets, raised everyone’s standard of living substantially.

There were, however, problems with a pure barter system. Here are a few examples:

- If you have a 400 pound hog, worth, perhaps 10 bushels of wheat, but you need only one bushel, what do you do? It wouldn’t be practical, for example, to cut off a front shoulder from your living hog to trade for the bushel of wheat, would it? Of course, you could butcher, process, and preserve your hog, but that’s not your business. You are a grower.

- Everyone has to carry all of their stuff around with them to every booth until they are finally traded out.

- The prices of everything had to be quoted in terms of everything else, which created a nightmare of valuation and quotation.

Just a thought: What do you suppose would have happened if you had offered to trade the wheat merchant nothing for his wheat? Or how about and IOU scribbled on a scrap piece of paper? Might you have been successful?

The point here is that people were trading something for something. Remember that. It’s important, and you”ll see it again later.

A golden future

At first, all things traded were, for the most part, things that had immediate practical value – you could eat it, you could wear it, or, like a tool, you could use it in productive ways. It came to pass, however, that another kind of commodity began to be perceived as having value, though not because it had the kind of utility mentioned above, but simply because people liked it. They thought it was pretty and enjoyed possessing and even wearing it. This commodity was gold and, to a lesser extent, silver.

Soon, another kind of vendor began appearing at markets everywhere – the gold merchant – and they always did a brisk business. Gold became so popular that it came to be almost universally accepted by any merchant so that, no matter what a vendor had, he would readily, even eagerly, accept gold for it. For that reason, one of the first trades that people would make would be to trade, or sell, whatever they had for gold, which they would then take around to trade for, or buy, all of the things that they needed.

So, gold offered the following advantages:

- It was desirable

- It was convenient – you could carry a lot of value in a small package

- Prices of all things, instead of having to be quoted in terms of everything else, could now be quoted only in terms of gold (and, perhaps, silver)

- It held its value over long periods of time

- It was durable – it did not tarnish, rust, corrode, or rot

- If you lost it, it would always find its way back to you

(I’ll bet I had you going there for a second)

Some of the functions that a sound money must provide are:

- It must function as a medium of exchange – people would willingly accept it in exchange for their goods

- It must must function as a store of value – it must not lose its value over time

- It must function as a standard of deferred payments – people must be able to contract for future payments and/or quote future prices with confidence that the value of the unit of money would remain stable and not degrade

So, what do you think? Did gold satisfy these requirements? It’s easy to see, isn’t it, how gold evolved into the first money?

We must remember, though, that when people traded their stuff for gold and then traded the gold for other stuff, they were still trading something for something, or, if you prefer, something (their old stuff) for something (gold) for something (new stuff).

The next step – the origin of commercial banking

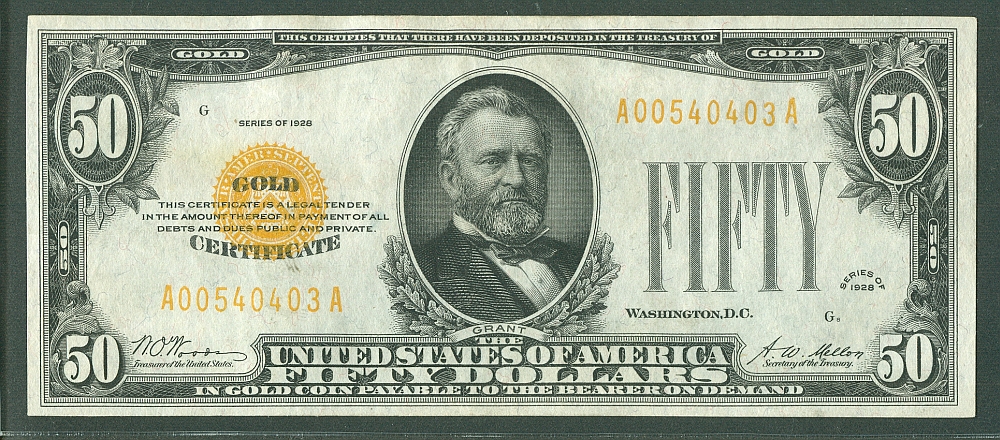

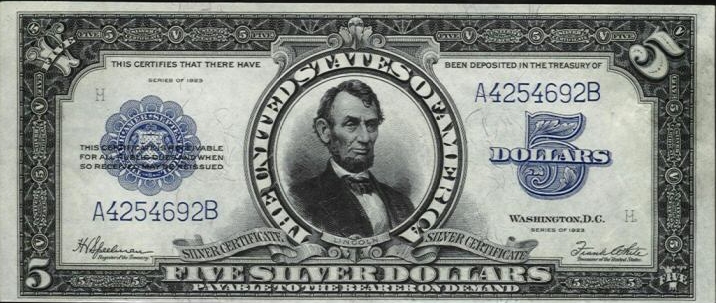

Even though carrying around many ounces of gold was more convenient than carrying around an entire wheat crop or a whole herd of cows, it was still not convenient enough for us, because we are, if nothing else, creatures of convenience. So, what we would do is this: We would sell our crop for gold, and then we would deposit the gold with the gold merchant, who would give us warehouse receipts for our deposit of gold. We might even choose to get many receipts in a variety of denominations. Then, instead of carrying around many ounces of gold, we could carry a fraction of an ounce of paper, and we could trade the receipts for whatever we wanted to purchase in the market place, because people new that the receipts were exchangeable for gold. The new owners of the receipts could, at their pleasure, take them to the merchant and retrieve their gold.

Because the receipts were infallibly redeemable for gold at the full face value, people were still trading something for something.

So, that’s how gold became the first practical hard money and also how an asset-backed paper money probably evolved. As long as a person could easily and unfailingly take a one ounce denominated receipt to the gold merchant and quickly and easily get one ounce of gold, all was well. As you might suspect, however, humans being the stinkers that we are, we just couldn’t leave well-enough alone.

The unfortunate, but inevitable, invention of funny money

By and by, the gold merchants, who you have by now recognized as our first bankers, began to make an interesting observation. First, though, let me back up a bit. The gold merchants had possessed, of course, their own stock of gold, which they would add to by charging transaction fees for their banking functions. Rather than allow this gold to remain idle in the vault, they began to lend it out to credit-worthy people who needed more gold than they had crops to trade for. At this point, however, there was never more than one ounce of receipts existing for each ounce of gold on deposit.

So still something for something.

Now, to the interesting observation: The gold merchants (bankers) began to notice that, because the receipts were so popular and were traded over and over, few people came in to redeem them and actually withdraw their gold. At this point, use your imagination to picture them all stroking their chins and sayng “hmmmmm” while the wheels in their heads turned. The result of all of this chin stroking, hmmmm-ing, and wheel turning was that they began to try a little experiment. They began to issue and lend more receipts than they had gold to back, basically creating and lending receipts for gold that did not exist, and, for this “funny money” they would charge the same interest rate as always!

Here’s a question for you math whizzes:

When the “bankers” would charge, say, a twentieth of an ounce of gold per year as interest for each true ounce that they would lend, their return was five percent per year. On the other hand, if they created and lent out receipts for gold that did not exist and then charged the same twentieth of an ounce interest per year, what was their return then?

If you said that their return was impossible to calculate by even the most powerful super-computers because it was infinite, then pat yourself on the back, because you are correct. When the bankers charged a twentieth of an ounce of gold per year for lending a one ounce receipt that was created out of thin air and backed by nothing, their return was infinite and, therefore, so large that it was not even capable of being measured! That made the bankers smile. It also made them very wealthy and, therefore, very powerful. It is beyond the scope of this article to say where that great power led, but you can see the result today, and it is not good.

Fractionally speaking

[*note – If the following gets a bit confusing for you, then don’t worry about it, and don’t spend a lot of time trying to make sense of it. You already know the important things, so, if you prefer, feel free to skip ahead to “The Final Step …” below.]

The bankers found that, over time, people never redeemed more than, say, ten percent of the gold receipts outstanding, so they reasoned that they could safely issue, and lend, receipts for ten times the gold in their vaults, including that gold belonging to other people.

So, if they had 1,000 ounces of their own gold plus 9,000 ounces of gold deposited by others, then they could, they believed, safely issue receipts totaling 100,000 ounces of gold. Now recall that depositors held receipts for 9,000 ounces which were not loans, so the bankers could create receipts for 100,000 – 9,000 = 91,000 ounces that they could then lend out. Then, the bankers probably got together and agreed that if one began to have a little trouble with excess redemptions, then the others would come to his rescue.

This creation of currency out of thin air for values far in excess of the reserves held is called fractional reserve banking, and it is still practiced today, only the true situation today is actually much worse than that related above.

The final step in the destruction of sound and lawful money

Over time, the paper receipts, or currency, came to be thought of as the money instead of the gold that they were supposed to stand for, most of which didn’t even exist. Keep in mind that, at this point, gold of at least ten percent of the total of outstanding receipts, or currency, had to be kept in reserve, so gold was still an effective limiter upon the amount of receipts, or currency, that the bankers could create, and they did not want to see their supply dwindle.

Gold served to limit money creation in two ways:

- If the bankers did not keep enough in reserve to cover the small percentage of redemptions, then they could become bankrupt in a hurry.

- If the bankers issued too much currency, then, even if they were still able to cover redemptions, something else might happen. Since the bankers were decreasing the value of the currency, general prices would tend to rise, and people would begin to realize that the receipts, or currency, were buying less and less while gold was holding its purchasing power. This would lead them to increase their redemptions of currency for gold, and the bankers would have to watch their reserves go away. In banking, this is called disintermediation. Another way of saying it is that “bad money drives out good,” a banking principle known as Gresham’s Law.

Quite naturally, according to human nature, the bankers did not want any limitations upon their ability to create money out of thin air, so I imagine that they got together and came up with a game plan – convince the government to stop the requirement that money be convertible into gold altogether. Of course, this would require that all gold in the peoples’ hands be confiscated so that the government would be the only legal owner of gold.

Anyway, once the requirement for redemption in gold was eliminated, then the warehouse receipts, now currency, were no longer backed by anything at all, and there would no longer be any limitation upon the amount of valueless paper money that the gold merchants, or “banks”, could create.

So, for the first time in history, people could be persuaded to trade something – their crops, animals, clothing, tools, etc. …

for absolutely nothing!

… and, as long as people could be kept ignorant of what was really happening, the bankers, who were now actually creating money, and, later, the government, could manipulate the money supply as they pleased to their own ends and profit.

Basically, this system of fractional reserve banking fueled by currencies that were no longer backed by gold is what eventually evolved in every developed country all over the world.

Today

How has this system worked? Pretty well, for the most part, at least from the bankers’ perspective. As long as people did not become frightened for some reason or another, or become wise to what was actually happening, and therefore begin, in large numbers, to redeem their certificates, the sheep could continue to be shorn, year after year, decade after decade. Of course, as more and more money was created out of thin air, prices of everything would rise, but the people would never seem to be able to understand why it was happening and who was causing it and understand that, as the purchasing power of their money dwindled, they were literally being stolen from! Sadly, they still do not today.

Money that is not 100% backed by hard assets is called “fiat money.” “Fiat” means by government decree. So fiat money is, then, money only because the government says that it is. Would you care to guess what kind of money the United States government provides for its people today and why?

For this study, it serves no useful purpose to give dates when this was accomplished here. Just know that it was. As I said, this is kind of a loose version of actual historical events, and, if you want to investigate further, there are ample resources available online. I would personally recommend The Ludwig von Mises Institute at Auburn University. Their web site is mises.org. Also The Foundation for Economic Education, or FEE, based in Atlanta, Georgia, at fee.org.

In Part 2, we’ll discuss that phenomenon known as inflation and its moral status.

Jere Moore has been blogging about political matters since 2008. His posts include commentary about current news items, conservative opinion pieces, satirical articles, stories that illustrate conservative principles, and posts about history, rights, and economics.