I supported Congressman Ron Paul because he is the only true constitutionalist in the presidential race, but I do not agree with him on everything. Recently, I read Congressman Paul’s book, The Revolution, and am now reading his book, Liberty Defined. I have found these to be both interesting and informative and would highly recommend them to any patriot, but, as I was reading them, there were a few things that I just couldn’t get on-board with.

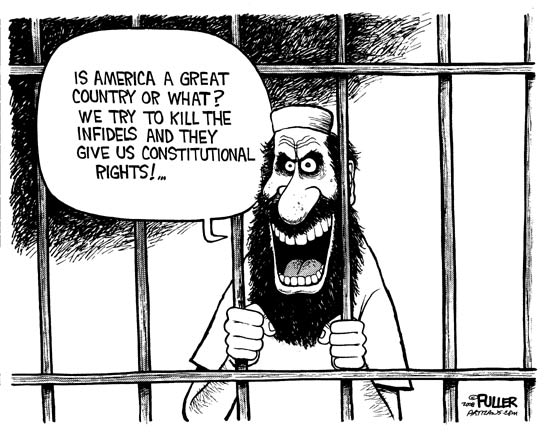

Before we go any farther, let’s correct something. Even though it is very popular to say “constitutional rights”, there are no such things, and it is improper to say it. The Constitution doesn’t convey any rights. What it does, and very importantly so, is provide the means to protect and preserve our Natural Rights, which belong to us by virtue of our humanity and, therefore, have nothing at all to do with government. So, let’s continue.

One of the things that I couldn’t get on-board with was the Congressman’s notion that terrorist suspects should be afforded constitutional protections. According to Paul, they should be treated as any other criminal – apprehended, charged, tried, convicted, and punished under the same laws as other criminals. Unquestionably, some should be, but, I would argue, not all.

If an American citizen were to be apprehended in the US while doing terrorist things, then I might agree with Congressman Paul. On the other hand, what if the US citizen were to be apprehended, or otherwise dealt with, on foreign soil while clearly working with a country or organization that was, according to their actions, unquestionably at war with America? Should that person enjoy Constitutional protections? In my mind, that is a different question altogether.

Consider Awlaki …

Let us consider the case, as the congressman points out, of Anwar al-Awlaki, a United States citizen who was recently assassinated via missile in the country of Yemen, a hotbed of terrorist activity. In order to attempt to answer the question at hand, we must first hearken back to a time before man had created society, when man existed within that state which John Locke called “the state of nature.” You’re probably thinking that there was no law during that time, but, of course, there was. There was, certainly, no man-made law, yet, because that is created by the same compact, or pursuant to the same contract that creates society, but there was that law that preexisted both society and man. I’m speaking, of course, of Natural Law, that unwritten body of moral principles from which all human rights are logically derived. Under Natural Law, man has, for example, the rights to life, liberty, and that which is the result of man’s life and liberty – property.

While man still existed within a state of nature, each, according to Locke, possessed the moral authority to administer justice according to his own principles and conscience. If one believed that he had been wronged by another, then he had the moral authority to exact punishment upon, and/or retribution from, the wrongful aggressor. Of course, the so-called aggressor may have seen it differently, but, since there was, as yet, no court system or other means of arbitration available, the two parties just had to work it out as best they could, and the result was that the strongest usually received the “justice”. Tyranny appears in many forms and, within this system, or rather lack of a system, it appeared as “a tyranny of the strong”. That was one of the reasons that man created society.

While in a state of nature, man’s rights were pure and unadulterated, and any man’s rights and liberty were limited only by the legitimate rights and liberty of others. In other words, each could do pretty much as he pleased so long as his efforts to enjoy his rights did not negatively impact the efforts of others to do the same.

Then came society

Later, due to the many advantages of living in cooperation with others, man would decide to create society. A society is created by what is called a “social compact,” which is an agreement that all who wish to live within, and enjoy the benefits of, the society agree to live by. The compact might provide for things like:

- Protection of peoples’ lives and property from outsiders

- Protection of peoples’ lives and property from each other

- A means of arbitrating good-faith disputes

- And so on

These benefits, and others, are provided by laws enacted within the society for this purpose. To distinguish this kind of law from Natural Law, we can call it “man’s law”, or “civil law.” Under the social compact, members of the society agree to allow certain of their Natural Rights to be abridged in order to protect all of the rest. They would, for example, delegate things like exacting punishment upon, and retribution from, wrong-doers, as well as arbitration of good faith disputes, to the government that is created by the compact. Anyone who found the rules too stringent for their taste was free to leave that society and move to somewhere else more to their liking, but, so long as he chose to live within the society, to be a member of the society, and enjoy the benefits of the society, he would be required to be subject to the terms of the compact. Some examples of well-known social compacts are the English Magna Carta, the Mayflower Compact, the Articles of Confederation, and the United States Constitution.

Rights cannot be taken, but …

Before continuing, let us jump back to that state of nature for a moment. According to Locke, even though man’s rights to life, liberty, and property, and others, were inalienable to him and could not, therefore, be separated from him, or taken away, it was possible for him, through his actions (mainly unjust aggression upon another), to forfeit them, or more accurately, to forfeit the moral authority to practice them. For example, if one man perpetrated an act of unjust aggression upon a second man, then the second man would have the moral authority, under Natural Law, to defend his life and property with whatever degree of force was necessary, with whatever force is necessary, up to and including lethal force, against the aggressor, who would have been considered to have, by his actions, forfeited his rights to life and/or liberty. Later philosophers would introduce the principle of proportionality which would hold that the punishment and/or retribution exacted due to a crime must be not be disproportionate to the crime, so that it would not be considered just, for example, for a person to take another’s life for only stealing a fifty-cent candy bar.

Back to the present

If you expect to get a gumball out of the machine, you must first put money in. So, no person who is not an American citizen can expect to enjoy the same protections, at considerable expense to everyone else, as one who is a citizen under our Constitution.

But, does not a non-citizen still have Natural Rights? Yes, certainly, and he is welcome to attempt to press them in any manner that he sees fit, but he cannot expect for the American society to press them on his behalf and bear the cost of that. As a non-citizen, his relationship to American society could best be described as being the same as that existing between two individuals while still in the state of nature.

But, you say, Awlaki was a United States citizen. So, what about him? When any two entities are in disagreement over some matter or other, whether they be states or individuals, they are, as English philosopher Thomas Hobbes might say, in a state of war, one with the other. When this happens between two individuals within the society, then the dispute is a matter of man’s law, and normal criminal or civil procedures should apply. On the other hand, when an individual who is a citizen of a society, in effect, declares war upon the whole of that society, especially if from foreign soil, then, I would argue, he has, by his actions, extricated himself from that society, placed himself back into a state of nature as to his relationship with that society, and so has forfeited coverage by that society’s protections.

So, what is the answer to our question? For a non-citizen, it is this:

No person who does not choose to be a member of society, say, for example, by becoming a citizen, can expect to be afforded the benefits of the society, and …

No person who has by his actions, in effect, extricated himself from that society can expect to be afforded the benefits of the society. That person has forfeited his constitutional protections and has morally, if not legally, become a non-citizen.

So, while I am not particularly fond of the idea of the Executive Branch having the kind of power to deal with anyone outside of the Constitution, I find the argument unconvincing that non-citizens, and even citizens like Awlaki, should be deemed as having the same protections enjoyed by other citizens under our Constitution.

I do, however, agree completely with Congressman Paul that, if there is even the slightest grain of doubt in matters such as these, then we should make absolutely certain that we always err on the side of liberty and not the other way around. It would be far, far better, for example, to acquit ten, or even a hundred or more, guilty people than to convict a single innocent person. Those guilty who are acquitted will always receive a just punishment sooner or later, if not in this life then in the next. Of course, there is always the risk that they will go on to commit other crimes, even murder, but that is, I believe, a risk that we must bear in the name of liberty.

In the same spirit, it would be far, far better to afford constitutional protections to many who may not deserve it than to deny it to one who does. Let us never forget that liberty does not come to us at a cheap price and that the toll can sometimes be very painful to pay, but pay it we must.

Jere Moore has been blogging about political matters since 2008. His posts include commentary about current news items, conservative opinion pieces, satirical articles, stories that illustrate conservative principles, and posts about history, rights, and economics.